accountability as a democratic necessity

i'm still here (2024) and holding the state accountable

A teensy announcement ahead of today’s newsletter:

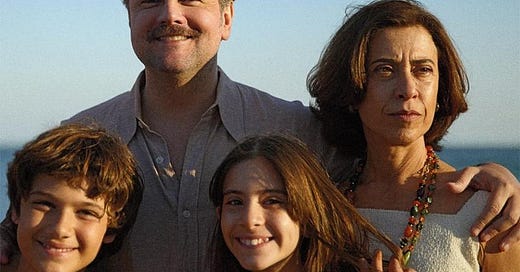

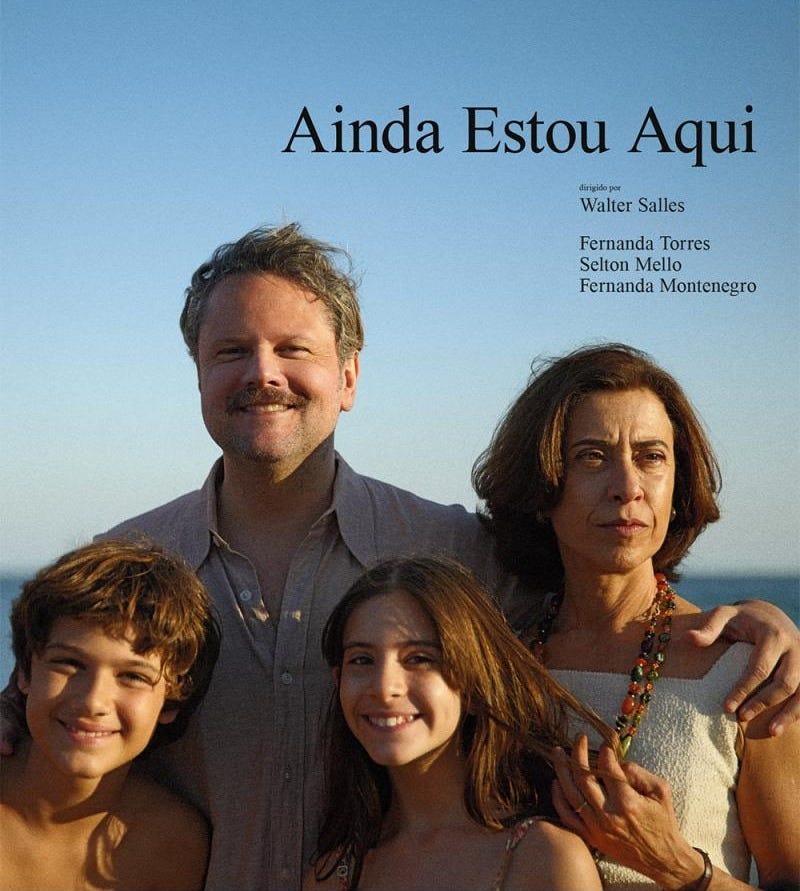

and I will be doing a little Substack live at 12:30pm EST later today (March 2), a bit of a pre-Oscars chat about the movies we’ve spent the last few months talking about. Join us if you’re able!On Friday night, I was finally able to see the Brazilian film Ainda Estou Aqui (2024), translated into English as I’m Still Here. Set mostly in Rio de Janeiro in the early 1970s, it focuses on the aftermath of a political prisoner’s unlawful detainment, torture, and disappearance by the country’s military dictatorship and his wife Eunice’s ensuing decades-long fight for the state to publicly and unequivocally admit its guilt for his disappearance and murder.1

The film sits in concert, I think, with 2022’s Argentina, 1985, which in turn took as its focus the immediate aftermath of that country’s military dictatorship and the prosecution of its leaders.

For the uninitiated, here’s a bit of a quick timeline of the military dictatorships, not all of them made equally but certainly interconnected, that ran through much of Latin America in the second half of the twentieth century:2

Argentina: March 1976-December 1983

Bolivia: August 1971-November 1978

Brazil: April 1964-March 1985

Chile: September 1973-March 1990

Paraguay: August 1954-February 1989

Uruguay: June 1973-March 19853

The film, I thought, was excellent. Its recreation of early 1970s Rio is spectacular, and it does a fairly bone-chillingly good job of showing how, even in the middle of disappearances, torture, and creeping loss of individual rights and civil liberties, life, for most people, does go on. If adjustments are needed, they are made, but the business of life by necessity must continue. It is nevertheless jarring.

*

There is one point that in my opinion the film made better than any other, and maybe I think this because of the moment we find ourselves in. Through its portrayal of Eunice’s decades-long fight for the state to admit its treatment and killing of her husband, the film emphasizes the value of seeking accountability from the state and its bad actors following wrongdoing. Immediately is best, but even if it takes decades, even if it is delayed by time and bureaucracy—accountability is always worth pursuing. It is a form, perhaps the most useful form, of justice. Even if the bulk of the effort is shouldered by a single person, pursuit of accountability is not a selfish or an individual act. It benefits not just the particularly aggrieved, but all unnamed and all potential victims. It serves the future. In this way, accountability could almost be considered a public good.4

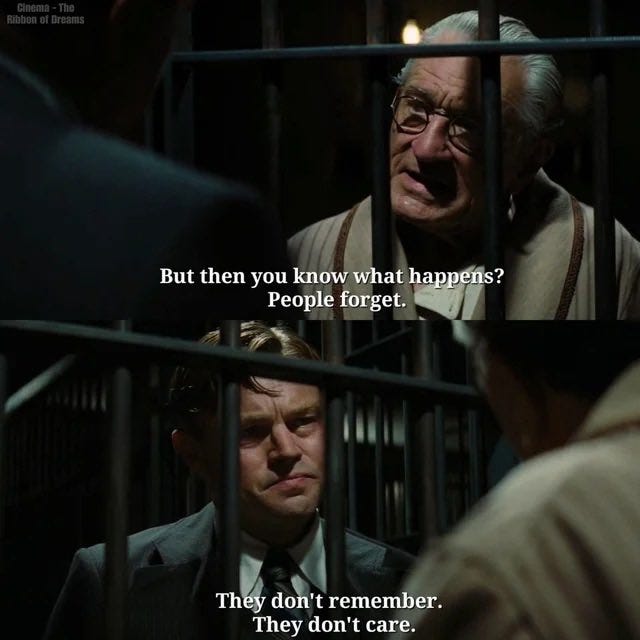

It doesn’t always work, of course. People do not like to remember times of national strife. They are ashamed of it, of having somehow allowed it and of living through it. They prefer to move on. Collective amnesia is a convenient thing. In a way, I’m Still Here served as a sort of foil to Killers of the Flower Moon (2023), a film I’m still thinking about a year and change after first watching it. Towards the end of that film, Robert De Niro’s William Hale, finally under investigation for the murder of dozens of Osage people and feeling not an ounce of regret, tells his nephew Ernest, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, that people will soon forget about his crimes. About him.

It’s a remark that time continues to prove right. If the arc of the moral universe is indeed long, it’s at least partly because people prefer their memories kept short. It feels shameful to have once lived in society with people who eschew and abuse human rights with impunity. We think of evil and corruption and violence as this contagious thing, maybe because it is, maybe each and every one of the aggressors are human, too, which means that so are their actions. But it’s uncomfortable to think of ourselves—average, perhaps even good people—as having anything in common, anything at all, with those power-hungry enough to throw entire societies into a realm of fear and chaos, with no regard for morality. So, once enough time has passed, once the shock has worn out, we say, well, shouldn’t we let bygones be bygones? Shouldn’t we focus on today’s troubles instead of wasting time on the past? We don’t see that they are one and the same.

*

There’s a scene near the end of I’m Still Here. Over 25 years after her husband’s disappearance, the state finally grants Eunice his death certificate, confirming that he died at the hands of the armed forces when he was unlawfully detained in 1970. Through back channels of information, she has known this nearly as long as he’s been missing, but she has spent the time in between seeking the state’s official admission of guilt, not just for her husband but for the thousands of people disappeared by the regime.

At the press conference for the presentation of this death certificate, which has the disarming visual of Eunice holding the document with a wide, almost giddy smile, a journalist asks, and I’m paraphrasing from memory, “Given all the current issues we have to deal with today, do you think it’s a valuable use of resources to spend time litigating the past to find closure on acts that might be best left to history?”

Eunice replies definitively in the affirmative, and says something like, “If we don’t make every effort to hold the guilty parties accountable, there is nothing keeping such events from happening again, right under our noses.” It’s not a new formula, exactly—those who don’t learn are doomed to repeat, etcetc. But it does seem to bear repeating.

*

I won’t compare the crimes of a military dictatorship to those of corrupt politicians in their more or less individual capacity. They’re not comparable. One has to wonder, though, what would’ve happened in the United States if its political leaders had reacted with more urgency to Donald Trump’s 2021 coup attempt, as Brazil did by enacting an eight-year election ban to former president Jair Bolsonaro when he falsely claimed Brazil’s electoral system was vulnerable to fraud. Similarly, one also has to wonder how someone like Andrew Cuomo, who in 2021 was forced to resign from his role as governor of New York following multiple allegations of sexual harassment against women, is now running for mayor of New York City.

I could go on. I exist, for instance, in a state of perpetual disbelief when it comes to George W. Bush’s evolution from war criminal into a sort of kindly Texan Picasso. Blows my mind. Shoutout to his PR team, I guess.

It is uncomfortable to maintain more than a passing familiarity with the sins of the past. The very fact that they took place implicates a lot of us. But too many people in power continue to behave as though the past is a defining and necessary condition of state-sanctioned violence; they are too easy in the imagined safety the present allegedly shields them with.

Meanwhile, trans rights are crumbling before our eyes, companies are rushing to voluntarily comply with xenophobic executive orders, our president’s favorite unelected and unappointed billionaire South African adviser is showing up at German far-right rallies, and immigrants are being sent to Guantanamo Bay, a detention camp famously unencumbered by the Geneva Convention. Is this not state-sanctioned violence, too? Or can we only call it that in history books, once enough years have passed?

It’s difficult to call on the past for protection when we never even owned up to it in the first place. In a healthy, democratic society, holding bad state actors accountable is not a luxury, something to do if you happen to have the time. It’s a necessity.

Further reading:

“Exposing the Legacy of Operation Condor” (New York Times, January 24, 2014) — Operation Condor was the name given to the coordinated campaign of political repression by right-wing and/or military leaders among the six countries listed above. This is an interview with a Portuguese photographer who aimed to document the consequences and results of the campaign.

“Transcript: U.S. OK’d ‘Dirty War’” (Miami Herald, December 4, 2003) — regarding declassified communications between then-Secretary of State Kissinger and the Argentinian junta.

“Why the Threat of U.S. Intervention in Venezuela Revives Historical Tensions in the Region” (TIME, January 25, 2019)

Oxford University’s Operation Condor Research Study — I thought this was interesting in that it lay out the archiving and general record-collecting efforts required in the pursuit of accountability.

A SHORT HISTORY OF CIA INTERVENTION IN SIXTEEN FOREIGN COUNTRIES (kinda nice of the CIA to put this together for us)

There are lots of other declassified documents, but I’m conscious of the diminishing marginal utility of further links.

If you’re still here, thank you for reading. I’m always a bit nervous when posting this kind of newsletter as opposed to those on lighter subjects.

You can find me on instagram and tiktok. The newsletter is fully supported by readers, so if you find yourself frequently enjoying these posts, please consider sharing the newsletter with a friend and/or becoming a paid subscriber.

P.S. Liking posts apparently makes a big difference for the ~algorithm~, so if you’ve enjoyed this issue and you’re inclined to hit the little heart, it wouldn’t be remiss!

I’d be remiss not to mention the recently resurfaced comedy sketch in which Fernanda Torres, who stars as Eunice, plays a character in blackface. It occurred in 2008 and frankly, I’m Still Here is indebted to Emilia Perez for being an even bigger shitshow and allowing this to fly mostly under the radar.

You might be thinking: wow, that’s a coincidence. How interesting. And while I’d love for us to exist in the world of coincidences, really I would, I do have to point your attention to the contemporaneous Cold War and the United States’ staunch belief that anything, including military and civic-military fascist dictatorships that tortured, killed, and unlawfully detained people, was better than a foreign country’s potential alignment with communism and the Soviet Union. As such, many of the Latin American military leaders were trained and supported—financially and diplomatically—by the United States. I won’t be getting into it today, but I’ll leave a few reputable, legitimate links at the end of the piece.

As a reminder, I am indeed from Uruguay, so feel free to take that into account as you read this. A bias of sorts, I suppose.

I’m almost wary of making this point, because I don’t really want it to be extrapolated as the justification of a justice system that upholds the carceral state. I’m not talking about punishment, which in my mind is a concept far and apart from accountability, and I’m not even talking about crime. I’m talking about the state and its penchant for violence as a means to consolidate power, and society’s reluctance to address the latter. I think that’s pretty clearly implied in my writing, but some points are best made explicit.

"It’s difficult to call on the past for protection when we never even owned up to it in the first place. In a healthy, democratic society, holding bad state actors accountable is not a luxury, something to do if you happen to have the time. It’s a necessity."

So damn true.

If anything, forgetting the past makes it even easier for war criminals like GWB to transform themselves into a "kindly Texan Picasso." Add Kissinger to that list. He got to die at home, warm in his bed. A courtesy not afforded to those in areas he targeted.

To your: “If you’re still here..” section, I’m still here!